Eleanor S. Armstrong, PhD student at University College London, and PgCert graduate, Art and Science, Central Saint Martins (class of 2016)

Extra-curricular activities can be beneficial for students in allowing them to apply skills and knowledge learnt on their courses. Student societies provide an important avenue for this learning and this paper reflects on the inaugural TEDxUAL in 2015, run by a dedicated society within the Arts SU at UAL. By looking at the format and execution of this event this article explores how such experiences encourage collaborative learning by members of the team. This paper looks particularly at how UAL’s key learning objectives can also be achieved by students through student-led project work such as TEDxUAL, and how annual projects such as this, are able to lead to growth and development of the students involved in its production.

TEDx; collaborative learning; skill development; Kolb cycle; learning experience; iterative development

TED is a non-profit organisation devoted to spreading ideas, usually in the form of short, powerful talks (18 minutes or less). TED began in 1984 as a conference where Technology, Entertainment and Design converged, and today covers almost all topics — from science to business to global issues — in more than 100 languages (ted.com, 2017). Attendance to the annual TED conference is by invitation only, with each ticket costing several thousand dollars. As of 2012, over one million people watch and share videos from TED conferences, masterclasses, and other TED-led events, on the TED platform everyday (en.wikipedia.org, 2017). TEDx is a global network where individuals are granted licence to run a TED-style event in their local community. In 2016 there were 832 TEDx University events around the world, 37 of which were held in the UK. Only two of these were based at arts colleges, UAL and the Courtauld Institute. I am writing this paper as the Lead Organiser for the TEDxUAL programme, with a core team of 9 students and staff, we collaboratively executed the UAL event, which was held on 12 March 2016 (TEDx.com, 2017). As a non-profit, but ticketed, event this ‘State of the Art’ instalment and more broadly the UAL institution share in the ethos promoted by the TED organisation, which aims to encourage ‘deeper understanding of the world’ by emphasizing ‘the power of ideas to change attitudes, lives and, ultimately, the world’ (TED, 2017). Over its lifetime, UAL has developed a distinct higher education environment that focuses on supporting students in entering the competitive fields of fine arts and creative industries by giving them ‘valuable learning experiences’ and ‘deepening’ their understanding of these industries. UAL follows on from Borzak’s description of higher education (1981), by enabling a ‘direct encounter with the phenomena being studied rather than merely thinking […] or only considering the possibility of doing something about it’ (in Brookfield, 1983, p.9).

As detailed in UAL Learning, Teaching and Enhancement Strategy 2015–2022, the core aims of UAL education are to foster ‘partnership’, ‘collaboration’, ‘practical experience’ and ‘employability’ (2015, p.3). Some of the key learning objectives detailed here, are successfully encouraged through such student-led programmes, such as TEDxUAL, and might be further supported by UAL’s more active involvement in future.

Initially, I will discuss how this collaborative philosophy was applied in delivering TEDxUAL and detail how the project provided a unique point of departure for the students involved. Finally, I shall conclude with some suggestions for improvement that could be implemented by subsequent groups, who have led, and will lead future instalments of the TEDxUAL project and further enable the project’s success.

As an institution made up of many colleges, who are in constant dialogue with one another, UAL embraces a collaborative pedagogy more strongly than most universities. Across the University there is an understanding that individual approaches of making/working are not dominant modes of production within the arts and creative industries. The UAL Strategy 2015–2022 highlights four aims in terms of enhancing teaching and learning that are particularly pertinent for this paper:

- collaborative processes allowing ‘expertise, inventiveness and unique perspective to enrich the student learning experience’;

- partnership, understanding the need to ‘establish effective partnership working within and across the colleges and departments of UAL’;

- practical experience, emphasising ‘enquiry-based learning’ and ‘activities should lead to concrete, accessible and useable ideas, tools and resources that can make an immediate and meaningful difference to the learning and teaching environment’;

- employability, including ensuring to ‘embed employability in the curriculum’, and that students are being ‘offer[ed] awards and funding opportunities’ to ‘develop their employability’.

(UAL, 2015, p.3)

What Fleming describes as a ‘more inclusive view of the arts which embodies making, responding, performing and appraising’ in a collaborative manner (2008, p.56) is evident in many UAL courses, where students are ‘given responsibility for some of the work involved, and are not passive recipients of a service’ (UAL, 2015, p.5). Assessments are often developed as a series of constraints that students work within, enabling them to develop practical methods of resolution when they encounter problems in production of their work, for example the ‘Rules of Random’ project on MA Art and Science (Barnett and Bennett, 2017). The fine art ‘crit’ is also used as a point of analysis during processes – conducted by peers, teachers and external experts. In the ‘crit’ there is a collaborative philosophy within the evaluation, emphasising collective contribution to critique over individual response. By embracing this collaborative notion that students learn best through interaction and interpersonal engagement in critical thinking, learning and writing; the TEDxUAL project has developed as another means through which students could embrace relational learning.

Whilst studying Art and Science at Central Saint Martins, the TEDxUAL project was conceived as an extracurricular, unpaid activity at the start of the year. It was not intended to be affiliated with any single course, department or college within UAL. I set-up a stall at the Arts Student Union Freshers’ Fair in October and over 2,000 people registered their interest to either attend or help organise the event. I invited all those who’d expressed an interest at the Freshers’ Fair to a meeting that discussed the different key roles needed within the team to get TEDxUAL off the ground. I received approximately 30 applications for the positions and invited everyone who applied for an interview at the High Holborn campus where the Arts SU is based. As leader and initiator of the project, I selected nine team members, based at 3 of UAL’s 6 colleges (LCC, LCF and CSM), with a variety of specialisms (including Fine Art, Graphic Design, Live Events, Fashion Marketing). From mid-October 2015 until the event on the 12 March 2016, the team collectively developed the event, from speaker selection and raising funds for the project to organising the venues, filming, a stage-set and producing a design theme. The core team brought in other volunteers for the day, and had additional marketing and production volunteers in the lead up to the event.

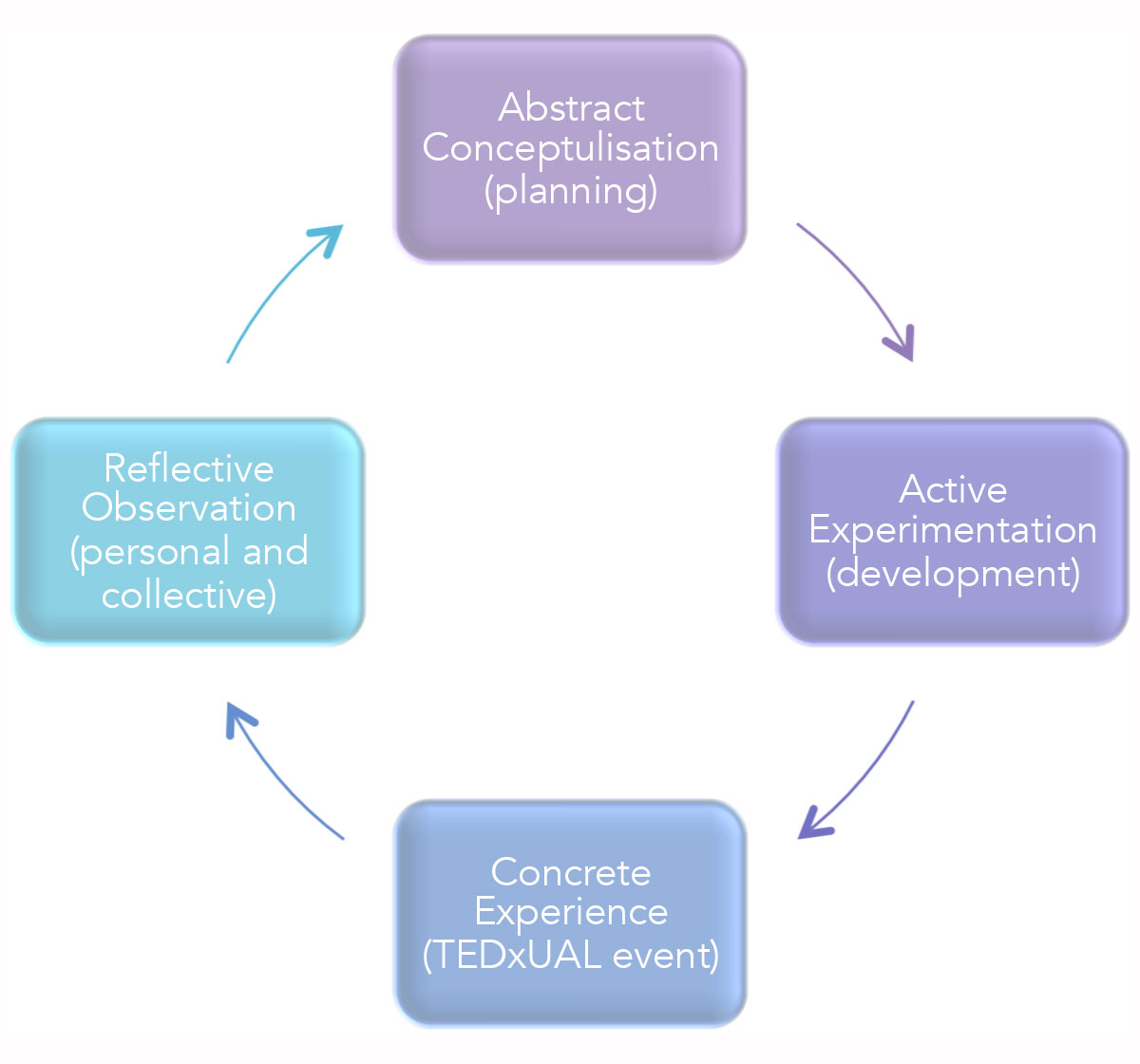

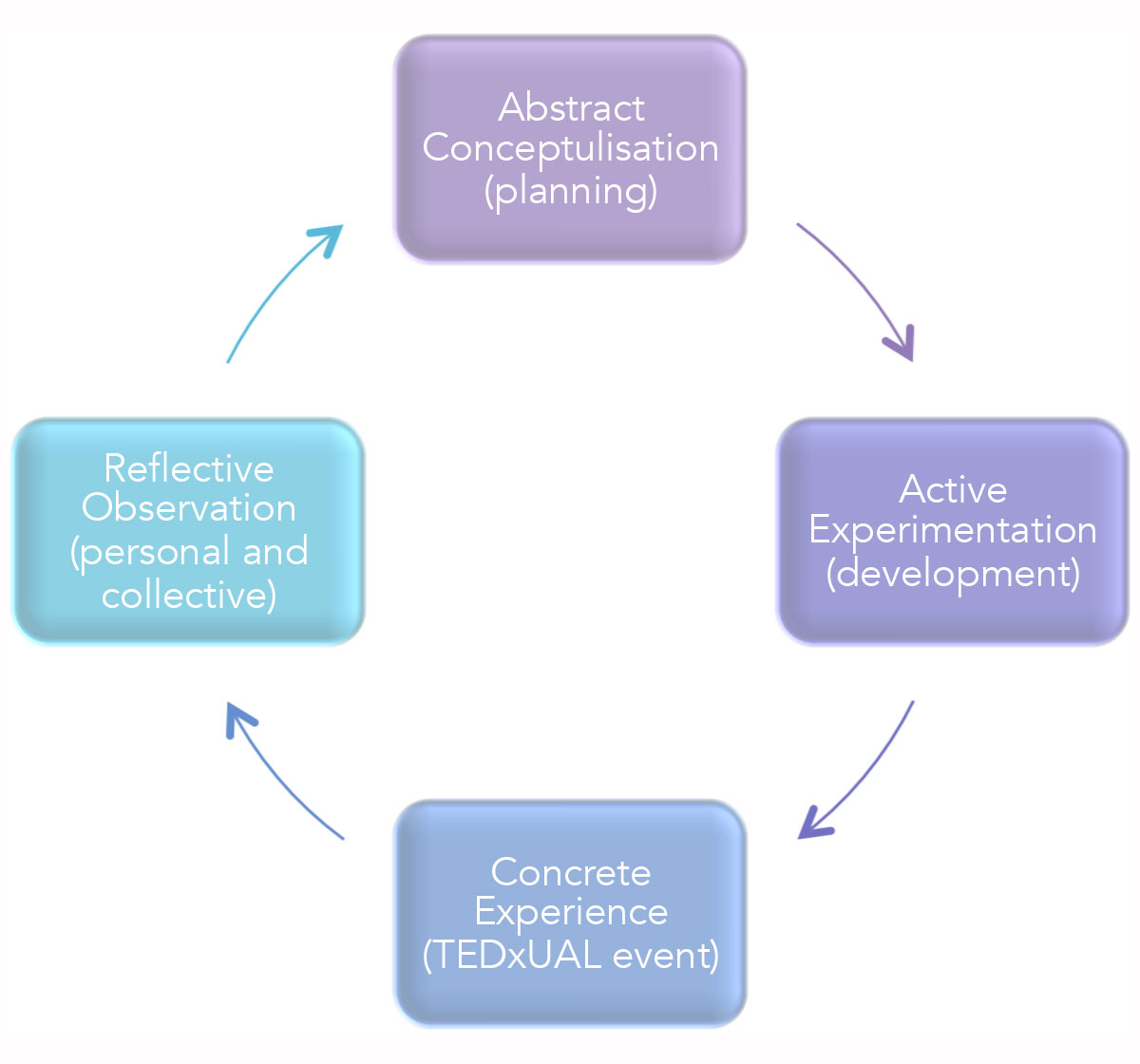

Kolb’s cycle of learning posits that concrete experience leads to observation and reflection. From this a new ‘theory’ (or understanding of actions) is deduced, which then acts as a guideline to creating new experiences (Kolb, 1984, p.21). Kolb’s Experiential Learning emphasises the importance of process, noting that ‘ideas are not fixed and immutable elements of thought, but are formed and re-formed through experience…no two thoughts are ever the same, since experience always intervenes’ (Kolb, 1984, p. 28). This paper adapts Kolb, in Figure 1, to demonstrate how TEDxUAL feeds back into team members’ student work in their UAL courses.

Where Kolb started by using Concrete Experience as the jumping off point for the theory – prioritising it as the personal experience that realises the abstract concept – TEDxUAL necessarily took Abstract Conceptualisation as its starting point as there was no collective concrete experience to generalise from at the start of October 2015. Having realised the TEDxUAL event throughout the development process from abstract concept into actuality and had the concrete experiences of delivering the TEDxUAL event, team members are now able to feedback these reflective observations into future TEDxUAL events, or into any further project they undertake within their course at UAL. The concrete experience of TEDxUAL, and its process of development, developed us as individual students, who are now better able to conceptualise and experiment within their own work as a result of experiencing and reflecting on TEDxUAL. We are also able to develop new processes for future collaborative group projects by understanding some of the pitfalls of the TEDxUAL collaborative project.

There is an emphasis on the importance of group work at UAL, as outlined in the teaching strategy, it seeks to support ‘collaborative, participatory and enquiry-led’ learning experiences (UAL, 2015, p.3). The TEDxUAL team had no prior experience of working with each other and came from different colleges and courses, and so we had to work to develop as a group. We met more often at the start of the project, in order to engender familiarity, instigate trust and build professional respect. We met in more formal ‘crit’ sessions, sharing the work that each member of the team had put into the project, and also arranged a few social events and went for dinner or drinks following meetings. We attended TED-based events, participating in TEDxEastEnd, joining a TEDx UK Organisers group meeting and watched a cinema live stream of TED 2016. This gave the group a focal point for discussions that were not our own work. These additional events were important for the success of the group and the ease with which we worked together. As we became familiar with each other, criticism was not taken personally, enthusiasm was felt more keenly and the reward of working together with people you care about became a motivating factor. This affinity instilled the group with a strong commitment in achieving the goal and our shared vision for TEDxUAL.

TEDxUAL event constraints also echoed the tangible constraints of UAL course-based collaborative projects. Some of them were externally set by TEDx, including the maximum number of tickets that could be sold; limitations on the length of the talks, the specification that the talks had to be filmed and edited in a particular manner and TED design guidelines. Some were set by the UAL, for instance the length of time we had the space for the event, and some were self-determined by the group, for example the theme for the event – ‘State of the Art’, chosen to explore the cutting edge of arts, design, science and social practice – and the speakers. These provided sufficient boundaries for the TEDxUAL team. As the leader of the group, I was able to act as a reminder for these limitations, helping guide the group’s work. As a unit, we set our own aims for the conference, focusing on the application of an arts education to other fields. We recognised that we were unlikely to raise very large sums to fund the event, so focused on local speakers and using volunteers so the event would run at the lowest cost possible, with the aim of making it sustainable as well as inspiring and enabling the TEDxUAL brand to continue to grow. From this work I identified that we had key learning outcomes within our group, including demonstrable experience and success in funding applications, partnership development and budget management.

For the first three months, our weekly crit-style sessions allowed each member to present their progress to the group, whereupon they received feedback and we discussed it internally. Along our journey to completing TEDxUAL we had other, larger and external ‘crit’ style sessions, including presenting our project in January to the Arts SU in a bid for funding, where we received external feedback on our project. We applied for sponsorship from a variety of organisations, however our initial ventures were turned down. Arts SU helped us because we were a student society, by suggesting other brands to apply for sponsorships and partnerships with and funding pots for us to apply to where we were more successful. However, as a result of not getting large sponsorship deals, but still having to cover significant costs of venue hire, equipment hire and personnel (technicians for the stage and filming) we had to charge for attendance of the event. As a student society, we were required to keep this money with the Arts SU for the duration of the event.

The production of the logo and the design surrounding the event demonstrates how we overcame problems and points of disagreement so often encountered during collaborative practice. In contrast to ‘crits’ in classes – where the disagreement then requires resolution by those whose work it is (where resolution includes actioning or not-actioning the disagreements between creator and audience raised in the crit) – this time disagreements had to be resolved by the whole group in order to proceed. Our design team, who were UAL students selected at the interview stages in October, presented their designs to the group with time to justify their choices of the style and the thematic representation. Other members of the team then had the opportunity to explore questions including:

Through this process the designers were able to iterate their design for the next ‘crit’ and re-present. This process was particularly important for the designers, as they were also using their design for the TEDxUAL event as a submission for their course project work (where students submitted work produced for extracurricular projects). For them the iterative process was an invaluable discussion point aiding the development of their submission. In this way, we encouraged collaborative resolution of a problem that was integral to the project.

Evaluation of the project came through a number of sources – from attendees of the event who were invited to share feedback through TEDx which was then passed on to us; from peers who fed back to us personally afterwards; and from staff of the University, including those from Arts SU.

Focusing first on attendee feedback, we received a series of comments on disparate parts of the event. Much of the feedback was positive: ‘top talks and speakers’; ‘well organised’; ‘big Variety [sic] of topics’; ‘very interesting presentations on all sorts of subjects and topics’; ‘the event was executed on a highly professional level, the selection of talks was varied, stimulating and high quality, the venue was complimentary and easy to network in, and the organisers friendly!’ (TEDxUAL, attendee feedback, Armstrong, 2015).

Helpfully, some of the comments also indicated where the TEDxUAL project could improve for the next run:

It was a well organised and well executed event. Hopefully talks will also get more diverse with later sessions.

I enjoyed the event very much but I think the next venue needs to have seating that allows for more leg room and the timings could be more synchronised on the website, emails and program. The variety of speakers was very rich but some of the strength of the presentations was lost due to the speaker's nerves and how they handled the nerves. I wasn't sure about the graphics used on the free bags and whether they reflected the day's topic. Overall I had a good, informative day.

(TEDxUAL, attendee feedback, Armstrong, 2015).

This last comment provided a strong base for some resolution points for the 2017 programme. We are unable to change the venue, as it is the only space that will provide us with suitable footage for the videos, although possibly this could be discussed with the University. To increase the breadth of the topics covered we decided as a group, to open a call for speakers from the UAL student body. Some of these speakers had been more nervous at speaking alongside older or more practiced speakers. For 2017 we noted that there needs to be more preparation and training for those who are less used to talking in public. We ran an open application for the artwork on bags that contained the booklet and sponsored items on the day – meaning it was not designed by the designers on the team. This appears to have been jarring for the participants, and as a result of this experiential learning process the 2017 team kept more editorial control over the design process. Our aim to share more about how arts education can be explored in other fields appears to have been a negative outcome for some of the audience members. For the 2017 programme, the theme of ‘Momentum’ was broader, in order to resolve these problems.

From members of the University staff, I have less direct feedback (often these were positive expressions in personal communications or face-to-face), but as the new 2017 committee have produced the next TEDxUAL the staff members who invested in the project, financially and emotionally, have done so again. This suggests that they received the first TEDxUAL, and our collaborative output and learnings well, and are keen to support it.

Within the group we fed back to each other about the project, observing how the TEDxUAL collaborative learning scheme gave individuals a chance to develop collaboratively, in line with the UAL’s educational ethos – providing a platform for ‘bringing together their expertise, inventiveness and unique perspectives’ (UAL, 2015, p.5). By working collaboratively one group member returned that this had allowed the group to ‘grow an idea from being average to being inspiring’ within the team (TEDxUAL, participant feedback, Armstrong, 2015). This collaborative effort, over the course of the year, gave rise to a ‘community at UAL [that is able to] enhance collaborations and discussions based on inspiring ideas’ (UAL, 2015, p.5). Importantly, the energy of this group dynamic revived ideas that might have been running dry: one member returned that ‘sometimes the momentum of the group waned, but we always picked up after spending some time working together rather than apart’ (TEDxUAL, participant feedback, Armstrong, 2015). Ensuring that this community and collaborative spirit is held intact was crucial to the success of TEDxUAL, and many of the team care about the project’s future success, investing more into the project.

The initiative also lead to usable ideas and tools for individual the members of the group – giving them practical collaborative experience that they could transfer to other areas of their professional and personal life. Some members of the group reflected that the work they did within TEDxUAL complemented their studies and provided another testing group for the process studied in courses. It should also be noted that 33% of the core team went on to lead the 2017 programme (of the remainder, 44% graduated the UAL that year (TEDxUAL, participant feedback, Armstrong, 2015)). The enthusiasm and commitment of the group can be put down to the generation of these collaborative working methods and the production of a well-received project.

TEDxUAL has served as a case example, revealing how extracurricular activities enhance and improve key learning outcomes for the students involved. The suggestions which follow are likely to be appropriate for other extracurricular collaborative learning platforms that exist at UAL, as well as future instalments of TEDxUAL.

In the development of TEDxUAL for its next iteration, audience feedback (such as keeping the design more closely tied together, diversifying the speakers, and helping more nervous speakers build confidence before the event) improved the direction that the collaborative work for the 2017 event took. In future events from 2017 onwards it would be invaluable to get more concrete feedback from members of University and SU staff about the collaborative work the TEDxUAL team had done to better be able to build on their collaborative learning practices and feedback learnings from the event and how they relate to courses and course-based teaching. Possible methods of gathering this would involve implementing a more formal or planned process of feedback such as surveys or micro-interviews with the staff who helped in the delivery of TEDxUAL, or incorporating a tutor for the project who could feed back.

It is important to note that we were a small group – and to improve this in the 2017 event the team was significantly expanded so that there was less responsibility resting on each individual, increasing the collective learning from the event. The flip side to this might be that close collaboration across the team is lost and instead of echoing and furthering the UAL’s collaborative learning projects this becomes a more traditional team structure (as I was not a member of the team for the 2017 event, I cannot comment on the team structure).

More generally, it would have been beneficial to more clearly define the goals of the event at the start to focus the collaborative efforts. Although everyone on the 2016 team was aware of the aim to produce our event, we did not spend any substantial time defining the type of event we would like to host (did we want it to be intimate? Did we want people to get a chance to meet the speakers?). As a result, we had less guiding group knowledge on what should be prioritised. As a consequence we experienced some dissonance within the group at different junctures, such as deciding whether to prioritise work on recruiting and training volunteers for the day or training speakers. Being able to understand this before the event might lead to more harmonious collaborative working practices.

In conclusion, the collaborative learning project that we undertook through TEDxUAL produced not only an interesting and vibrant event, but also some valuable experiences for the group in learning about production of an event.

This opportunity provided me with a lens to understand better my personal aptitudes. My reflection has pushed me to view curation and organisation of events as part of my creative practice. TEDxUAL gave me the liberating experience of seeing all my curatorial endeavours as part of a cohesive whole. In light of this, I have learnt more how to run a collaborative project. TEDxUAL highlighted to me the importance of having experienced members of the team (e.g. our Event Manager was a professional event manager) but also giving those without professional experience (e.g. our designers) a platform for their work. I felt that sometimes these two groups grated on each other, but ultimately working alongside each other gave each side of that partnership a chance to learn more about how the other functioned, and widened the spread of the collaborative learning we were able to achieve. UAL has a variety of learning and professional experiences within its student body, and I think that TEDxUAL 2016 as a student society provided an incomparable platform for such students to meet.

As the initiator for TEDxUAL (a continuing student-led project which has since had an offshoot event at the British Museum in 2017), I have had time to reflect upon the experience, both personally and professionally. I connected with friends across UAL I would never otherwise have had the opportunity to meet, as well as networks beyond the core team, including fellow students at clubs and society events; team-member networks; volunteers and attendees of the event itself. Without this my UAL experience would have been emptier, and I would not have made such a wonderful selection of friends and collaborators. More recently, it has been exciting to see my work built upon by the subsequent Lead Organiser, Chloe Mattei, and her team who ran TEDxUAL 2017 in March, with the theme ‘Momentum’. A new team is now planning TEDxUAL 2018.

By introducing an arena where students could learn tools from each other’s different courses and develop a wider professional community at UAL, TEDxUAL has stepped beyond equipping individuals with a chance to practice the capabilities in their course, and created a forum for sharing and amalgamating through collaborative learning. Importantly, I think that projects like TEDxUAL not only provide invaluable training and learning experiences for students such as myself, but also enhance the institution itself. By demonstrating that students within UAL are able to execute a full conference to a high standard – with a substantial online presence – student-led projects like TEDxUAL heighten UAL’s brand to students and professionals. Its commitment to enabling students (present and future) to see that sharing research and generating new knowledge independently is as important as the teaching and training inside the classroom is, for me, an important expression of UAL’s commitment to the ‘synergies between the creative process of teaching and making’ (UAL, 2015, p.3).

Barnett, H. and Bennett, S. (2017). Forced Connections and Rules of Random. [online] MA Art and Science. Available at: http://www.artsciencecsm.com/forced-connections-and-rules-of-random/ [Accessed 1 Jul 2017].

Brookfield, S. (1983) Adult learners: adult education and the community. Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

Fleming, M. (2008) Arts in education and creativity: a literature review. Arts Council England. Available at: http://www.creativitycultureeducation.org/wp-content/uploads/arts-in-education-and-creativity-2nd-edition-91.pdf (Accessed: 22 June 2017).

En.wikipedia.org. (2017). TED (conference). [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/TED_(conference)#2000-16:_Recent_growth [Accessed 1 Jul 2017].

Kolb, D.A. (1984) Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Peck, W.C., Flower, L. and Higgins, L. (2009) ‘Community literacy’ in Miller, S. (ed.) The Norton book of composition studies. New York: Norton and Company. pp.1097–1116.

Streeting, W. and Wise, G. (2009) Rethinking the values of higher education – consumption, partnership, community? Gloucester: Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education, QAA. Available at: http://www.sparqs.ac.uk/ch/F2%20Rethinking%20the%20Values%20of%20Higher%20Education.pdf (Accessed: 22 June 2017).

Ted.com. (2017) Our organization. [online] Available at: https://www.ted.com/about/our-organization (Accessed 1 Jul. 2017).

TEDx (2017) TEDxUAL 2016 ‘State of the art’. Available at: https://www.tedxual.com/2016-state-of-the-art (Accessed: 22 June 2017).

University of the Arts London, UAL (2015) UAL learning, teaching and enhancement strategy 2015–22: delivering transformative education. London: UAL Teaching and Learning Exchange. Available at: http://www.arts.ac.uk/media/arts/about-ual/teaching-and-learning-exchange/2015---2022-Learning,-Teaching-and-Enhancement-Strategy.pdf (Accessed: 22 June 2017).

Eleanor S. Armstrong is a PhD candidate at University College London, studying collaborations between artists and scientists. She’s interested in collaborations across knowledge areas, which developed during her time on the MA Art and Science course at Central Saint Martins. Prior to studying at UAL, she read Chemistry at Oxford University, specialising in the Astrochemistry of Saturn’s Upper Atmosphere. In addition to her PhD research, Eleanor currently works as an Explainer at the Science Museum, and organises Creative Reactions – a project that takes art-science collaboration to the pub under the Pint of Science banner.